A FREE-LABOR FARM.

----,

--. I have been visiting a farm, cultivated entirely by free-labor. The

proprietor told me that he was first led to disuse slave-labor, not from any

economical considerations, but because he had become convinced that there was

an essential wrong in holding men in forced servitude with any other purpose

than to benefit them alone, and because he was not willing to allow his own

children to be educated as slave-masters. His father had been a large

slave-holder, and he felt very strongly the bad influence it had had on his own

character. He wished me to be

satisfied that Jefferson uttered a

great truth when he asserted that slavery was more pernicious to the white race

than the black. Although, therefore, a chief part of his  inheritance had been

in slaves, he had liberated them all.

inheritance had been

in slaves, he had liberated them all.

Most

of them had, by his advice, gone to Africa. These he had frequently heard from.

Except a child that had been drowned, they were, at his last account, all

alive, in general good health, and satisfactorily prospering. He had lately

received a letter from one of them, who told him that he was "trying to

preach the Gospel," and who had evidently greatly improved, both

intellectually and morally, since he left here. With regard to those going

North, and the common opinion that they encountered much misery, and would be

much better off here, he said that it entirely depended on the general

character and habits of the individual; it was true of those who were badly

brought up, and who had acquired indolent and vicious habits, especially if

they were drunkards, but, if of some intelligence and well-trained, they

generally represented themselves to be successful and contented.

He

mentioned two remarkable cases, that had come under his own observation, of

this kind. One was that of a man who had been free, but, by some fraud and

informality of his papers, was reenslaved. He ran away, and afterwards

negotiated, by correspondence, with his master, and purchased his freedom. This

man he had accidentally met, fifteen years afterwards, in a Northern city; he

was engaged in profitable and increasing business, and showed him, by his

books, that he was possessed of property to the amount of ten thousand dollars.

He was living a great deal more comfortably and wisely than ever his old master

had done. The other case was that of a colored woman, who had

obtained her freedom, and who became apprehensive that she also was about to be fraudulently made a slave again. She fled to Philadelphia, where she was nearly starved, at first. A little girl, who heard her begging in the streets to be allowed to work for bread, told her that her mother was wanting some washing done, and she followed her home. The mother, not knowing her, was afraid to trust her with the articles to be washed. She prayed so earnestly for the job, however--suggesting that she might be locked into a room until she had completed it--that it was given her.

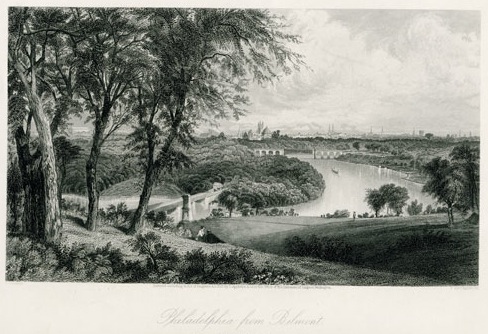

A view of Philadelphia

So

she commenced life in Philadelphia. Ten years afterwards he had accidentally

met her there; she recognized him immediately, recalled herself to his

recollection, manifested the greatest joy at seeing him, and asked him to come

to her house, which he found a handsome three-story building, furnished really

with elegance; and she pointed out to him, from the window, three houses in the

vicinity that she owned and rented. She showed great anxiety to have her

children well educated, and was employing the best instructors for them which

she could procure in Philadelphia.

![]() A Free labor farm Olmsted Journey in the

Seaboard Slave States.

A Free labor farm Olmsted Journey in the

Seaboard Slave States.

1853-1854.